September 12, 2013

September 12, 2013

Michael G. Santos

For our third class on The Architecture of Incarceration, I wanted my students at San Francisco State University to grasp an understanding of how easily past events and experiences influenced perceptions about what was possible. The young men and women participating in our class were reared in a tough-on-crime era. They did not strike me as being particularly disturbed by our nation’s massive prison system. I wanted them to grasp that we didn’t always lead the world in incarcerating more people per capita than nation on earth. To illustrate how experiences influenced our perceptions and abilities to think creatively, I asked a few students to step to the front of the class so that we could reenact Plato’s allegory of the cave.

Plato’s Allegory of the Cave

The projector was on, and the five students who volunteered stood between the projector’s beam of light and the classroom’s blackboard. As Plato wrote in his analogy from his classic book The Republic, I asked students to imagine that the volunteers who stood before them had been reared in a cave. For their entire lives, the students had been fastened in such ways that they could not move their bodies or turn their heads. They’ve only seen the shadows on the wall, and as such, they believed those shadows on the wall were real. One of the prisoners of the cave eventually was able to break free from the bondage. He saw that the experience of living in bondage had influenced all of his perceptions. With his newfound liberty, the escaped prisoner was able to explore the world and enjoy different experiences. When he returned to the cave to inform the others that they’d been living an illusion, however, the escaped prisoner found that those still living in bondage rejected his message. Instead, the prisoners of the cave clung to the delusions that they had known all of their lives.

That simple enactment, I hoped, helped me convey why so many people believed that our nation’s response to criminal behavior was the only appropriate response. It was all they knew. I wanted to show the absurdity of our nation’s commitment to policies that keep so many people incarcerated for lengthy sentences. Although lengthy sentences and massive prison populations have been a staple in our society for as long as my students had lived, I explained that our nation didn’t always incarcerate more of its citizens than any other nation on earth. We then transitioned into a discussion about how our tough-on-crime policies began.

That simple enactment, I hoped, helped me convey why so many people believed that our nation’s response to criminal behavior was the only appropriate response. It was all they knew. I wanted to show the absurdity of our nation’s commitment to policies that keep so many people incarcerated for lengthy sentences. Although lengthy sentences and massive prison populations have been a staple in our society for as long as my students had lived, I explained that our nation didn’t always incarcerate more of its citizens than any other nation on earth. We then transitioned into a discussion about how our tough-on-crime policies began.

Evolution of Punishment

I spoke a bit more about Robert Martinson, whose work in the early 1970s had an enormous influence in shifting policy for our nation’s criminal justice system. Martinson was a social scientist who participated in a study called “The Effectiveness of Correctional Treatment: A Survey of Treatment Evaluation Studies.” After reviewing the findings from 231 different rehabilitation programs, Martinson published some startling conclusions. He wrote that “Rehabilitative efforts that have been reported so far have no appreciable effect on recidivism.”

Ironically, people from both the right and the left side of the political spectrum embraced Martinson’s work. Many opposed rehabilitative programs that influenced indeterminate sentencing systems because they believed they were unfair. With an indeterminate sentence, judges imposed minimum and maximum terms of confinement. Administrators then relied upon records prisoners accumulated inside of the institution to determine whether the prisoners should be released at the low end of the indeterminate sentence or at the high end. Those on the left who embraced Martinson’s findings believed that rehabilitative programs were unjust because an administrator could look at a prisoner and charge him with having a bad attitude. That attitude could result in the offender serving a much longer sentence.

For different reasons, those on the right embraced Martinson’s study. They did not like the idea of an offender having opportunities to manipulate his way through rehabilitative programs strictly for the purpose of reducing the amount of time he would have to serve. Conservatives wanted to see tougher sanctions across the board, and Martinson’s study helped them to make the case.

Martinson’s study developed real panache in the media with its tag line “Nothing Works!” I explained to the class that I had a different perspective. I did not dispute that few people in prison participated in rehabilitative programs. As an example, I told them that I began serving my sentence in a high-security penitentiary with more than 2,500 other prisoners. When I began serving the term, Pell Grant funding was still available to people in prison. As a consequence of that funding, prisoners were eligible to participate in university programs without having to pay any out-of-pocket costs. Any prisoner in that institution could’ve enrolled in the university program and earned a bachelor’s degree if only he was willing to do the work. Yet during the time that I served there, I was the only prisoner inside of those walls to earn a bachelor’s degree.

Why? I asked the students.

After some brief discussion, I elaborated more on the culture of confinement. Although I began serving my sentence during an era when so-called rehabilitative programs existed in American prisons, even then no one emphasized the importance of preparing offenders for law-abiding, contributing lives upon release. College programs may have been available, but budgets went to the custody faction of the prison, not the rehabilitative side.

As David Rothman wrote in his book Asylums, prisons were total institutions where authorities governed every aspect of a prisoner’s life. They determined where he slept and when. They determined what he ate and when. They determined where he would work. They determined how he could communicate with the outside world. Authorities had the power to influence the subculture inside of prison walls. Rather than creating an atmosphere that would lead prisoners to embrace the values of a law-abiding society, administrators created a hostile us-versus-them atmosphere. Many prisoners perceived the culture of the penitentiary as being oppressive, exploitive, and dehumanizing. Accordingly, few could sustain the high level of energy and discipline necessary to prepare for success upon release. Instead, they focused on making it through the journey, one day at a time.

Accordingly, although Martinson’s study concluded that “Nothing Works” when it came to prisoner rehabilitation programs, I asked the students to consider a different perspective. Nothing worked, I pointed out, because American prisons never truly meant to rehabilitate anyone. Prisons were programmed to receive. As such, they perpetuated cycles of failure rather than contributed to community safety.

But John Martinson’s study inspired other conservative writers to advance theories on why society needed to invest even more resources to build a tougher prison system. The celebrated Harvard scholar James Q. Wilson published his influential book Thinking About Crime. In his book, Professor Wilson rightfully argued that many of the people who went to prison came from disadvantaged backgrounds and didn’t know any way of life other than that characterized by a pursuit of immediate gratification. Offenders had resisted the teachings of public schools and likely failed to learn from earlier exposures to the criminal justice system. Since they hadn’t learned in the past, Professor Wilson made the case that it was absurd to cling to hopes that prisoners would be receptive to educational or vocational programs while they served time in a penitentiary. Since society did not know how to reform criminals, it should not waste further resources in wasteful rehabilitative programs. Nothing works, he claimed. Rather, Professor Wilson argued that we should deploy more resources to keep prisoners incarcerated for longer periods of time.

Those tough-on-crime theories led to changes in legislation and to budgetary allocations. Legislators in state and federal governments moved away from indeterminate sentencing models which authorized judges to sentence offenders to terms that had both minimum- and maximum-sentence lengths. The Nothing Works era of the 1970s led to the abolition of parole boards and the introduction of determinate sentences, meaning that judges imposed fixed sentences that were much longer and that did not provide incentives or mechanisms for prisoners to reduce their terms through merit.

With more offenders going to prison who would serve sentence that were far longer than in the past, and with the removal of mechanisms like parole boards that could in theory encourage offenders to work toward reducing their sentences, prison population levels soared after the Martinson and Wilson influences. Accordingly, legislators began to adjust their allocation of taxpayer resources. They diverted tax dollars that would’ve been flowing into social programs like universities, hospitals, and social services and instead appropriated those tax dollars to fund a bigger, more expensive prison system.

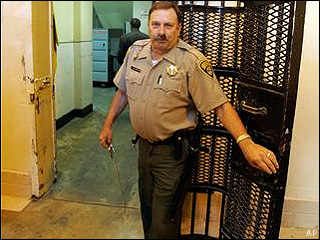

That bigger prison system employed more guards. Those guards contributed a portion of every check to a union. With financial contributions pouring in from an ever-expanding work force, the union of prison guards built thriving bank accounts. The union of prison guards deployed those growing financial resources to lobby legislators for more spending on prisons. It became “one of the most feared political forces in the state,” pouring millions into the campaign coffers of politicians who pledged to put more people behind bars. Those funds led to higher salaries for prison guards. The funds also led to the expansion of the prison system and the passing of more laws that would lead more people to prison.

But consequences followed the growing trend toward mass incarceration. I showed the students a film that profiled Professor Philip Zimbardo’s famous Stanford Prison Experiment. Perhaps the most famous prison experiment of all time, Professor Zimbardo’s work dramatized the ways that a prison culture could influence the ways that both guards and prisoners behaved.

Following the film showcasing the Stanford Prison Experiment, I discussed with students what I observed as a long-term prisoner. Rather than contemplating the negative influences of prison policies and the culture that followed those policies, prison guards obsessed on their role of maintaining order within the institution. Guards did not concern themselves with how that emphasis on order would influence adjustment patterns of prisoners or how those adjustment patterns would influence the ways that people in prison returned to society. Since prisoners did not perceive reasons to prepare for success upon release, they focused on making it through their sentences one day at a time.

Prisoners did not thrive in that culture of failure. As an offer of proof, we discussed a bit about the prisoners at USP Marion whose murderous behavior on a cellblock at the nation’s most secure prison led to the advancement of the supermax penitentiary. The students had read descriptions in my book Inside: Life Behind Bars in America, which was required reading for the course, but I showed a film to help bring those words to life. The film was a segment from 60 minutes that depicted the Segregated Housing Unit at Pelican Bay State Prison in Northern California.

My purpose in showing the film was I wanted them to contrast the horror of Mike Wallace and the psychologists who discussed Pelican Bay with the perception of guards who touted Pelican Bay as a success story in prison management. I wanted the students to listen as a car thief described the ways that he was tortured and maimed because of brutal prison guards who took prison policies of order too far. I wanted the students to see how prisons, as total institutions, could influence behavior of all who live or work inside of them. The guards may not start out as being brutal, but the atmosphere could make them so; the prisoners may not start out as predatory gang members, but the prison could make them so.

With that background, I introduced the students to a psychopath who was serving a life sentence at Corcoran State Prison. The man began serving his sentence for a nonviolent crime, but he described how the culture of prison influenced his adjustment. To distinguish himself in that culture of failure, the man became a murderous predator. He didn’t start out that way, but the subculture of prison influenced his behavior.

Then I brought the class back to those lessons from Plato’s Republic and the allegory of the cave. If taxpayers only heard the narrative of those who had an interest in building a bigger prison system, then taxpayers would never consider alternatives or options that we as a society could pursue to build a more effective prison system. A more effective prison system, I explained, would focus on promoting community safety. We could look to prisoners who changed their life for the better as examples of what an effective prison system could produce.

To highlight that message, I showed a presentation of James Anderson. He was a young gang member who spoke about being the most violent kid in juvenile hall, a young man whom authorities would point to and argue that he would never change. But those authorities were wrong, as leaders like Scott Budnick from the Anti-Recidivism Coallition and Julio Marcial from The California Wellness Foundation worked to mentor and guide him. As a consequence of their sponsorship, James Anderson broke away from the world of gangs and now works as an advocate to improve our nation’s prison system.

Then I spoke about the amazing work of Shon Hopwood, who wrote about his story in Law Man. Shon was an armed bank robber who educated himself while serving a lengthy prison sentence. As a consequence of Shon’s transformation, he found sponsors in society who took a vested interest in his success. Shon is currently a third-year law student at The University of Washington and has become quite a success story with an offer to begin clerking for a distinguish federal appeals court judge.

All of those stories, I wanted the students to see, showed that we could determine what we wanted our prison system to produce. We could focus on mass incarceration and see prison population levels and prison budgets continue to rise. Or we could focus on a system that aspired to enhance community safety. As an example, of such a system, I concluded the class with further discussions about Norway’s ombudsman system and the emphasis in that country of preparing offenders for law-abiding, contributing lives upon release. Then we held a class experiment where the students became part of an ombudsman panel. I gave them pertinent facts about a criminal case, then asked them, as citizens, to determine the appropriate sanction. After recording their findings, I revealed the actual sanction imposed upon the offender. The contrast between what the students thought of justice with what our system demanded broadened their awareness on the need for reforms within our nation’s prison system.