San Francisco State University

San Francisco State University

The Architecture of Imprisonment

Class 1 lecture: August 29, 2013

Michael G. Santos

Today I delivered my first lecture for students at San Francisco State University who enrolled in The Architecture of Imprisonment. In an effort to summarize the class for my students, for those who follow my work, and for those interested in an overview of how our criminal justice evolved, I’ll write this recap of the class.

My official roster indicated that 45 people enrolled in The Architecture of Imprisonment. Professor Jeffrey Snipes told me that I should expect that other students would want to add the class. I welcomed all students who showed an interest in my work. As a man who served a quarter century in prison, I feel as though I have a responsibility to share what I experienced, observed, and learned from interviewing others inside America’s federal prison system. Teaching brings a sense of fulfillment, as if I’m making a positive contribution to society.

By the time class began, at 4:10 in the afternoon, every seat appeared to be taken. I passed a roll sheet around the room. Sixty-nine students signed their name to the roster. The students who were not officially enrolled asked me to assign them permit numbers. Since I did not know how to assign permit numbers, I asked them to place a note beside their names on the roll sheet and I promised to find a response for them by the time we met for our second class on Thursday, September 5, 2013.

Beginning the class

Earlier, I sent a group email to the enrolled students that encouraged them to look me up and learn a bit more about me. As a matter of full disclosure, I wanted the students to know about my background. After all, they were making a significant investment in their education and they had a right to know that although I stood in front of the class lecturing, I had been released from the prison system only 17 days previously, on August 12, 2013. I attach a copy of the email I sent out below:

Hello Students,

My name is Michael Santos and I’m the instructor for Criminal Justice 0451, The Architecture of Imprisonment. I look forward to meeting each of you and to sharing all that I’ve learned about America’s prison system.

As I wrote in the class syllabus, I will teach this course from a perspective that may surprise some of you. The books I’ve assigned will describe my journey and provide reasons why I feel so passionate about helping more people understand America’s prison system. Those who want more immediate information may Google my name or visit a website that I’m developing at michaelsantos.com. I intend to publish articles on that website that we can use as resources for the class.

I look forward to spirited discussions and to helping each student understand more about America’s prison system.

Sincerely,

Michael G. Santos

Since I also wanted to know about the background of my students, I asked each student to share some information. Starting from the front of the class and working my way through the back of the class, I asked each students, one-by-one, for an introduction. I wanted to learn each student’s name, year of study, major of study, and career aspirations.

All but one of my students (who was a junior) were seniors, on the verge of graduating from the criminal justice program. Many aspired to pursue careers in law enforcement, with ideas of working for various police departments, for juvenile justice, for probation, and some for adult corrections. Some students wanted to advance to law school. Many students had not yet decided what type of careers they would choose.

Some had taken courses that described the jail system, but I did not get a sense that the students had spent much time discussing prisons. Since they were seniors in criminal justice, I suspected that the students knew more about our nation’s prison system than they were willing to reveal. After all, we were in the first day of class and I had not yet earned their trust. They may have been feeling me out as a lecturer.

My Background

Since the students had not yet read any material for the course, I reserved that first hour as a kind of get-to-know each other period. After the students responded to my question about their background, I told them about mine. Since reading material for the course included my books Earning Freedom: Conquering a 45-year Prison Term and Inside: Life Behind Bars in America, the students would learn quite a bit about my journey through county jails and federal prisons of every security level. Wanting to give them a thumbnail version of events, I explained the bad decisions I made as a young man that led to my arrest on August 11, 1987. I told them about my journey through jail, my exposure to the work of Socrates, and the commitment that I made to work toward reconciling with society.

The three-part plan that would guide me required that I devote every day of my sentence to work toward:

- Educating myself

- Contributing to society, and

- Building a support network that would have a vested interest in my success upon release.

I explained to the class that I believed such a principled, values-based approach would help to guide me from the darkness of imprisonment to the light of liberty. The deliberate adjustment strategy led to my earning an undergraduate degree from Mercer University in 1992 and a graduate degree from Hofstra University in 1995. Those credentials later led to my building a career in publishing. I wrote to help more citizens understand prisons, the people they hold, and strategies for growing through prison. As a consequence of those publications, numerous other opportunities opened to bring meaning and a sense of relevance to my life. Although I served decades in prison, I worked each day to live as one with society and to earn liberty.

My hopes had been that I would’ve received more interaction from the students. I assured them that they could ask me anything. I wanted them to know that I was an open book and eager to help them understand the prison system from an insider’s perspective. From the respectful attention they paid me, I sensed that they were listening, but I really wanted to engage with them. I concluded that first hour of the lecture with a commitment to work toward finding ways that would bring them in to the discussions.

At 4:55 we stopped for a five-minute break.

Overview of Punishment

During the second hour of our initial class, I lectured on the evolution of punishment in Western civilization. It being the first day of class, and knowing that I had not yet assigned any reading to the students, I did not intend to overwhelm them with the names of scholars who’ve studied and written about punishment from philosophical and social perspectives. But I did want students to know that we as a society did not always respond to those who broke society’s laws with incarceration. In the past, many Western societies responded to lawbreakers with corporal punishment.

I asked whether anyone in the class was familiar with the French social philosopher Michel Foucault. One of the well-read students shared her recollection of Foucault’s work in his famous book Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. In his 1975 book, Foucault provided readers with a graphic glimpse of how governments once responded to criminal offenses with public displays of torture. The first pages of that book portrayed a crowd gathering around to watch as authorities drilled holes into a man’s body, then filled those holes with molten steel. In the end, the authorities tied the man’s limbs to four separate horses, and then literally ripped the offender apart as the horses raced off in different directions.

Those types of violent corporal punishments characterized medieval societies, but in the 1700s, Western civilization moved into a period known as The Enlightenment era. During that time, artists, philosophers, and scientists contemplated steps we as a society could take to advance humanity. Some even argued that we could respond to criminal behavior in more civilized ways than inflicting pain or death on the body of lawbreakers.

An Italian philosopher, Cesare Beccaria, who lived in the mid 1700s, authored On Crimes and Punishment, a book that brought a different perspective to the ways that civilized society should respond to offenders Many scholars refer to him as being the father of the “classical school” of criminal justice theory. He opposed torture and the death penalty, arguing that criminal justice should confirm to rational principles rather than appease a lust for vengeance. With regard to the death penalty, Beccaria argued that the state did not have any more right to take lives than anyone else. He also maintained that killing people did not further the interests of civilization because it didn’t lower crime rates. Rather than seeking vengeance, a principled criminal justice system should strive to accomplish specific principles, including:

- Deterrence, meaning that punishment should deter others from committing crimes.

- Proportionate, meaning that the punishment should be a sufficient response to crime, but not become a spectacle.

- Certainty, meaning that offenders should know that punishment will follow criminal behavior.

- Public, meaning that all citizens should be aware of the punishment.

- Swift, meaning that the punishment should be carried out quickly after the offense was committed.

Following our brief discussion of Foucault and Beccaria, I spoke about Jeremy Bentham, a British social philosopher who was born around the time that Beccaria advanced his theories on reasons why we should reform our criminal justice system. Scholars frequently refer to Jeremy Bentham as being of the “neoclassical school” of criminal justice. Bentham is most famous for his philosophy known as Utilitarianism.

Both the classical and neoclassical school focused on crimes as being offenses against the law rather than offense against nature. The punishment of offenders should be swift, certain, and no more brutal than necessary to serve the greater good of society. Bentham advanced the classical thoughts of Beccaria by arguing that an enlightened society should not only punish behavior effectively to serve the greatest good for the greatest number, but society should also address crimes before they occurred through public investment in education and promotion of a benevolent society.

Bentham also advocated for the abolition of the death penalty, holding that corporal punishments failed to advance society in ways that would serve the interests of the majority of citizens. Instead, he argued for prisons that would afford opportunities for the state to reform offenders. Those who read about Bentham will see that he is well known for designing The Panopticon. The Panopticon prison was designed in such a way that guards could stand in a central tower right in the middle of a round prison. The prison cells would be distributed on tiers that surrounded the tower, providing a vantage point through which guards would always be able to observe what the offenders were doing. Many governments later made use of the Panopticon design. (See a publication by Kim Swanson, graduate student from Florida State University for more detail.)

When I asked the students in my class whether they were familiar with a country that established a penal colony, many of the young men and women were familiar with the policies of England during the 1800s. They transported offenders to Australia. I told them what I knew about Alexander Maconochie, a Scottish man who was credited for reforming the Australian penal colony known as Norfolk Island.

Professor Norval Morris, from the University of Chicago, mentored me while I was in graduate school at Hofstra and he introduced me to the work of Alexander Maconochie. In a book that Professor Morris wrote about Maconochie, I learned that Maconochie wanted to make fundamental reforms to the criminal justice system. Rather than striving to deter offenses or punish offenders, he believed that the prison experience should function with an objective of making offenders more fit to live in society as law-abiding citizens. With that goal in mind, Maconochie introduced the token economy, through which offenders on Norfolk Island could work to earn gradually increasing levels of liberty. Prisoners could earn higher levels of freedom through their efforts to atone for their criminal behavior, or to make things right with society.

I told the group how reading the work of Professor Norval Morris and the prison reforms that Alexander Maconochie introduced on Norfolk Island influenced my journey through prison. I always believed that if I worked hard, somehow I could find a way to function and add value in society. That pursuit of liberty did not result in my leaving prison one day sooner, but it instilled me with a high level of energy and discipline through each of the 9,500 days that I served. That work inspired me to continue studying about the prison system and the people it held. (For those who would like to read more about Alexander Maconochie, I suggest the following article: http://www.academia.edu/1073580/Alexander_Maconochies_Mark_System)

Evolution of Prisons in America

The concept of the prison began to grow in America during the late 1700s, with the first American penitentiary being constructed in Philadelphia. It was known as the Walnut Street Jail. It featured individual cells designed to provide offenders with a place to do penance for their punishment. The Quakers came up with this plan in Philadelphia, believing that confining a person would open opportunities for him to heal, or atone for his bad deeds.

Later, as our country’s population level grew, President Andrew Jackson presided over an era (1820s to 1830s) that led to the expansion of the penitentiary system on a massive scale. The first huge penitentiary, known as The Eastern State Penitentiary, was characterized by absolute solitude. Before guards admitted a prisoner into Eastern, they placed a gunnysack over his head. Then the guards led a prisoner to a solitary cell and locked him inside. Until the end of his sentence, a prisoner would not have any contact with the outside world. He would be left alone in the cell without anything but his thoughts and his Bible. The Pennsylvania system was known as the separatist system of confinement.

A competing penitentiary system, known as The New York system, operated at the Auburn Penitentiary. Both the New York system and the Pennsylvania system were characterized by locking men in cells, but in the New York system, known as the “congregate system,” prisoners were able to leave their cells to labor together and sometimes to eat together. Either way, time in prison was theoretically supposed to be more humane than corporal punishments. The hope was that as prisoners spent time alone, they would study the Bible and prepare to lead law-abiding lives after release. What those theories did not take into account was that confining men in cages gave an enormous power to those who confined; prisons were rampant with brutality.

As we advanced into the late 1800s, we entered an era known as The Reformatory Era. It began with the famous Elmira Reformatory in 1870. The reformatory movement would begin to usher in policies that led to more than simply withering away years in a cell. Authorities introduced reforms devoted to instill more discipline and rehabilitation of prisoners. At first the reformatories were used for younger men, but by the 1900s, those concepts would give way to the industrial prisons, also known as “The Big House.” They were like walled cities with factories inside that were supposed to defray the costs of operating the prisons. Those who’ve seen The Shawshank Redemption, have a good idea of life inside of those types of institutions.

Gresham Sykes, a celebrated penologist, wrote about the Big House in his book The Society of Captives. That classic text in penology illustrated “the pains of imprisonment” for men inside the Trenton State Prison in New Jersey, a typical Big House prison. The prisoners had considerable liberty to roam inside the walls of the prison, but the institutions deprived prisoners of goods and services that people in the broader society took for granted. As a response to those deprivations, Darwinian subcultures began to evolve, with the stronger prisoners beginning to dominate the weaker prisoners.

Big House prisons gradually gave way to so-called “correctional institutions” in the 1940s and 1950s. Daily regimentations became more relaxed, with increasing opportunities for educational programs and vocational development. They became softer human warehouses than existed in the past, less oppressive.

On January 7, 2010, the San Francisco Chronicle published an article about John Irwin. Some of the people in my class had heard about John Irwin, who was a product of those more humane prison warehouses. John robbed a gas station as a young man and served five years at Soledad state prison. While inside prison he began to study and he earned some college credits. After he was paroled, in 1957, he continued his studies at UCLA and he earned an undergraduate degree. He then began teaching at San Francisco State University. In 1967, John founded Project Rebound, a university program that would help those coming out of prison go to college. I was impressed by many of the students who raised their hands when I asked whether they knew about Project Rebound and the rich legacy that Professor Irwin left on the university. He was another inspiration for me while I served my sentence.

But soon after Professor Irwin launched his career at SFSU, I explained to the students, other academics were making headway toward launching our nation’s movement toward a new era of mass incarceration. Rather than instilling more programs that would inspire more offenders to work toward educating themselves, a movement began toward mass incarceration. Robert Martinson, a sociologist, published an article called “Nothing Works” in the spring of 1974 that had an enormous influence on the growth of the prison industrial complex. Basically, the general takeaway from his article was that regardless of what resources governments poured into reforming prisoners, nothing was going to turn them into law-abiding citizens. (For more information on Martinson, see http://www.prisonpolicy.org/scans/rehab.html)

Professor James Q. Wilson also contributed to society’s prison evolution in America. In his influential book Thinking About Crime, published in 1975, Professor Wilson argued that we didn’t know enough about how to reform offenders. He also rejected the liberal, or “positivist view” that external forces such as poverty or lack of education were responsible for criminal behavior. To reduce crime, Professor Wilson believed that we needed to increase the costs for offenders. One way of increasing those costs for offenders would be to pass legislation that would keep offenders locked in prisons for longer periods of time. Such penalties, supposedly, would deter others from breaking the law.

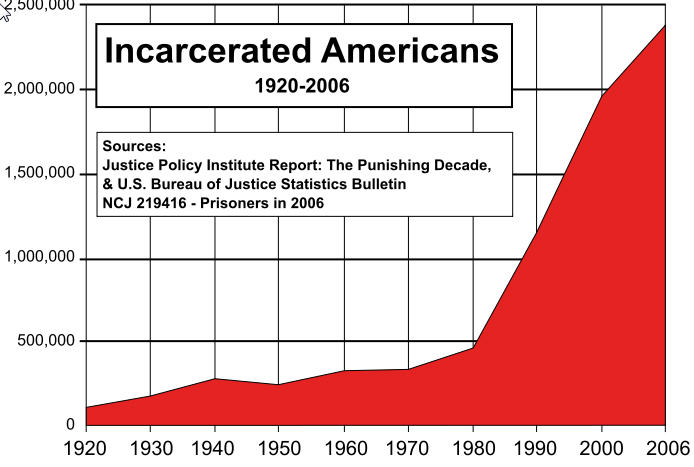

That policy of deterrence would lead to other consequences, too. It would usher in the movement toward mass incarceration. The chart I attach to this article shows how jail and prison population levels have risen since the start of our more punitive society that began in the 1970s. The War on Drugs, of course, really turbo charged the movement toward mass incarceration. I began serving my sentence, I told the class, right as prison population levels were beginning their hyperbolic rise. And on the day that I concluded 26 years in federal prison, on August 12, 2013, Eric Holder, our Attorney General, announced that we incarcerated far too many nonviolent drug offenders in America and that they served sentences that were far too long. He pledged that the Department of Justice was going to introduce policies to change the way our government prosecuted nonviolent drug offenders.

Summary

During this first session of our class at San Francisco State University called The Architecture of Incarceration, I wanted to provide the students with an overview. I told them about the history of punishment, briefly described some of the philosophers who advanced criminal justice theories, and I lectured on how the system evolved. With that basic understanding, I tasked the students with reading chapters one through four of my book Inside: Life Behind Bars in America before our class next week. Again, I invited the students to ask me anything about my journey, as I aspired to teach them from personal experience of living as a prisoner, and from all I learned by interviewing others who served time with me.

I thank Eddie Griffin, a man who recently was released from San Quentin State Prison, for joining me in class to share bits about his experiences in prison; and I thank Tulio Cardozo for bringing his camera to memorialize my first experience of lecturing at a university. I told the students that I invited other guest speakers to join us and to share their stories about the prison experience from different perspectives. Some defense attorneys, public defenders, and a chief probation officer have offered to share their experiences with the class in weeks to come.

Next week, for our second class, I look forward to discussing student reactions to the following:

- This recap of our first class

- A more informed discussion different criminal justice theories

- Chapters one through four of Inside: Life Behind Bars in America