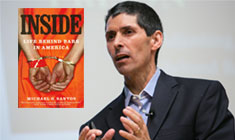

My name is Michael G. Santos and I’m writing this open letter for anyone facing struggles with the criminal justice system. I am not a lawyer, nor am I affiliated with courts or law enforcement. Rather, I am a man who made bad decisions in my early 20s. Consequently, three federal agents stopped me outside of my condo on Key Biscayne in 1987. First they pointed guns at my head. Then they ordered me to place my wrists behind my back. They locked me in chains while reading Miranda rights, telling me that I was under arrest. I continued making a series of bad decisions that led to my receiving a 45-year prison term.

I’m writing to share what I learned during that lengthy journey through prisons of every security level. Decisions I made inside led to my returning to society by way of a San Francisco Halfway House on August 13, 2012. I returned differently from what others would’ve expected from a man who served multiple decades in prison. Those who face challenges with the criminal justice system may want to know that despite current difficulties, they still have the power within to build meaningful, relevant lives.

The nature of my crime isn’t particularly germane to what I want to share. Yet as an offer of full disclosure, I’ll provide a brief summary of my background with the criminal justice system.

A reckless adolescence led to my living as if laws didn’t apply to me. At 17, I knowingly accepted a stolen stereo as payment for a gambling debt from another student while I was in high school. For that crime, the judicial system ordered that I send a monthly form in to a probation officer for nine months and that I pay $900 in restitution.

That exposure to law enforcement did not deter me sufficiently to lead a straight life. When the movie Scarface came out, I was 20 years old. That movie influenced choices I made. For the next couple of years I presided over a group of friends in a scheme to traffic in cocaine. Those decisions resulted in my arrest on August 11, 1987, when I was 23.

Anyone looking to learn more about my background may find details through books or articles that I’ve published. This letter includes my contact information for those who would like to know more, but an Internet search of my name would yield all the information anyone is looking to find.

Perspectives For Those Going to Federal Prison

Rather than writing about the crimes that brought me to prison, the message I’m sharing centers on perspective for those encountering troubles with the criminal justice system. I didn’t have the right perspective at the time of my arrest. Others who face struggles with the criminal justice system may want to know why perspective at the start of the journey makes such a difference with regard to how an individual concludes the journey.

Despite knowing that I had broken the law every day for two years prior to my arrest, I wasn’t ready to accept responsibility for my actions the day that I met those officers outside of my condo. Authorities didn’t catch me with cocaine, and since they didn’t have wiretaps or photographs that would implicate me, I clung to misperceptions that a jury wouldn’t convict me.

Expecting my attorney to use some type of legal abracadabra to free me, I pleaded not guilty. Going all-in, I exacerbated my problems by perjuring myself on the witness stand. At the conclusion of my proceedings, I still remember the jury foreman standing to read the verdict. I lost count at some point, but I know he said “guilty” more than 20 times. Those convictions exposed me to a possible sentence of life in prison.

Federal marshals locked me in chains and returned me to my jail cell that evening. While leaning against steel rails, feeling the cold concrete beneath me, I realized the magnitude of my predicament. By then it was too late. I couldn’t undo the crimes that I committed both before and after my arrest. Nothing would change the past. I prayed for guidance, not to be excused from the severe sanction certain to follow but for strength to carry me through the unknown ahead.

While still locked in that jail cell, during those dreadful weeks between conviction and sentencing, prayers brought a change of perspective. The catalyst was a chapter I read about Socrates in an anthology of philosophy. I had been a poor student through high school and I didn’t know anything about philosophy, yet when I read about Socrates’ trial I immediately identified with him. Socrates’ response to an offer he received to escape his punishment inspired me.

With Socrates as a role model, I aspired to serve whatever sentence the judge would impose with my dignity intact. Although I couldn’t disentangle myself from the past, I could begin to make better decisions that would influence my future. That perspective would guide me as the weeks turned into months, the months turned into years, and the years turned into decades.

Distorted Perspectives of Federal Prison

Unfortunately, observations and experience convince me that many people who proceed through the criminal justice system do not receive that message of self-empowerment. Some, like Aaron Swartz, take drastic action, choosing suicide rather than to endure the anguish of imprisonment. They mistakenly believe that their past decisions will prohibit them from living a meaningful, relevant life. I understand how such fears can distort reality.

The sound of hopelessness can echo off walls as they close in, suffocating the human spirit. Contemplations of being separated from society, being branded with a felony conviction, or having to start over can paralyze and torment the mind. All of those complications, including emotions like anger, shame, or bitterness can block individuals from seeing the path that leads to improved circumstances. That path begins at the fork of reconciliation and denial. Every individual must choose whether he will track a deliberate course toward reconciliation or allow the free currents of denial to carry him into deeper troubles.

We empower ourselves when we accept the situation accurately, as it is rather than as we would like it to be. If we can assess our situations accurately we can contemplate steps that are available to improve upon it. Then we can create a plan, taking incremental action steps along the way. Below I describe a strategy that I called my Straight-A Guide, a strategy that empowered me to tune out the negativity and myths of imprisonment.

Too many prisoners, regardless of education or background, buy into the myth that the best way to serve time is to forget about the world beyond prison boundaries. Convict lore holds that regardless of what an individual does, a person cannot influence change for the better while locked in confinement. Authorities do their part to keep that negative message alive, with correctional officers routinely telling prisoners “you’ve got nothing comin’.”

Yet history is replete with examples of people who served time in prison and emerged to lead not only their own lives, but to inspire and lead others as well. Viktor Frankl served three years as a prisoner of the Nazis, never knowing whether he’d live or die from one day to the next. He chose the path of serving others to ensure that each day of his life brought meaning. Mahatma Gandhi routinely went to jail for civil disobedience. Rather than complaining, he found strength by striving to live as the change that he wanted to see in the world. Nelson Mandela served longer than a quarter century, yet rather than living with bitterness or anger, he forgave those who incarcerated him and fought on to change a system that oppressed millions.

Role models like Socrates, Frankl, Gandhi, and Mandela offered a more powerful message than the convict code. They convinced me that an individual could indeed become something more than the negative influences around him. Rather than expecting the system to change his life:

- The individual needed to summon strength from within.

- The individual had to create meaning through being resourceful.

- The individual had to live as the change that he wanted to see in the world.

In my case, I couldn’t contemplate what it would mean to serve a 45-year sentence in its entirety. Instead of dwelling on the challenges I would face, I assessed my situation and tried to envision how I could make it better. I needed to define success, or the best possible outcome. I felt as if I had to cross a stormy sea of adversity. Success would mean reaching the other side of that storm, returning to society strong, independently, as a law-abiding citizen.

Three-part plan I used to conquer a federal prison sentence

Needing to clarify that vision further, I thought about the challenges I would face to make that aspiration a reality. Many people would have a hard time looking beyond my criminal conviction. In response to that expectation, I contemplated actions I could take to reconcile with society, to earn the respect of law-abiding citizens I admired. Those contemplations led to my three-part plan. If I worked:

- To educate myself

- To contribute to society, and

- To build a support network of law-abiding citizens,

I believed that people would consider me as something more than the bad decisions that brought me to prison.

To reconcile with society, I needed to give others reason to look beyond my criminal convictions. By establishing those three value categories, I could set clear goals that would guide me through my first decade. I would work to earn a university degree, to publish writings about the prison experience, and to bring 10 new mentors into my life. The strategy empowered me, allowing me to live as if I were the captain of my own ship. I would make decisions to influence my future rather than succumb to external forces that seemed to plot my demise.

Advising Others who Face Struggles of Incarceration

If I were to advise a man who faced struggle, I would share what I learned from my journey through a quarter century in prison. I would challenge any individual who took the time to read through this simple essay to take the same disciplined, principled approach that worked so well for me. Whether it’s a challenge from the criminal justice system, or anything else, the principles of this strategy apply. Define success by figuring out the best possible outcome.

Rather than allowing current troubles to define him as an individual, I would suggest the man pursue success. If a pursuit of success drove him, he would develop the strength to tune out noise, negativity, and hopelessness. It doesn’t matter what type of adversity he faced. Whether it was a reversal of fortune or criminal charges, the path to success—experience convinced me—began with perspective. Those who made deliberate, values-based decisions found the way to chart their own course, sustaining a high level of energy and discipline along the way. When the pursuit of success drove a man, he could muster the power from within to work through fatigue, to get more done, to exceed even his own expectations.

I can understand how easy it would be to dismiss, or even reject such a message from people who don’t understand an individual’s current troubles. A psychologist may offer similar advice, but he doesn’t know first hand what it is like to have the world crumble around him. Friends and family and lawyers may encourage an individual to find strength, but they don’t know what it’s like to exchange the comfort of home for life in a cage. Those who dispense advice have good intentions, but they have not experienced the cold, steel bars of a prison cell, day after day.

Yet mine is not the voice of someone who speaks without knowing the indignity of confinement. I have been chained, fingerprinted, and photographed in prisons of every security level across the United States. I’ve walked through puddles of blood, maneuvered my way through high-security penitentiaries, federal correctional institutions, detention centers, transit centers, and minimum-security camps. I faced challenges each day while advancing, inch-by-inch, for longer than a quarter century across a sea of adversity.

Despite such challenges, the values-based, disciplined approach that I began during that transformational time between my conviction and my sentence empowered me to persevere. Rather than blaming others for my predicament, I owned my decisions. Rather than waiting for a system to change me, I became resourceful. Rather than dwelling on what I had lost, I set my sights on what I could become.

That perspective made all of the difference. Because of that deliberate adjustment, I returned to society far differently from what anyone would expect. When I walked out of prison on August 13, 2012, I had a bachelor’s degree from Mercer University and a master’s degree from Hofstra University. I had a long string of published writings and university professors from across the nation used my work to educate students on America’s prison system. I had a support network that included dozens of leading citizens, and numerous employment offers. I even found the love of my life and married her inside of a prison visiting room while I still had longer than 10 years to serve. I emerged far differently from how I began, returning to society with values, skills, and resources that would translate into success.

In my book Earning Freedom: Conquering a 45-Year Prison Term, I tell the entire story, from the day of my arrest on August 11, 1987 through the day of my release, a quarter century later. As a consequence of the values-based, goal-oriented approach that drove me through each of the 9,135 days that I served, I’ve been able to build a career around lessons that I learned along the way. I call those lessons my Straight-A Guide to overcoming adversity. They’re really quite simple to follow. Those anticipating a stint on the inside, whether a 30-day term in the county jail or a 30-year sentence in the penitentiary, I recommend following this strategy to make the absolute best use of that excursion.

Straight-A Guide Strategy to Conquer a Federal Prison Sentence

Attitude: Begin with the right attitude. With the Straight-A Guide, we define the right attitude as a 100 percent commitment to emerging successfully, in accordance with the values and goal that an individual uses to define success. In my case, I made a 100 percent commitment to emerging as a law-abiding citizen, and I climbed inch-by-inch, doing whatever was necessary to advance such prospects.

Aspiration: Visualize precisely how you will emerge. To the extent that an individual can perceive success, he will have the reason to move forward, mustering the strength each day to advance. Twenty-five years before I walked out of prison, I had a vision of how I would emerge: with academic credentials, with published writings to my name, and with a broad support network that would have a vested interest in my success.

Action: Individuals who can define success can take incremental action steps that will lead them from where they are to where they aspire to be. A thousand-mile journey begins with the first step. For some, like me, that first step may be memorizing new words to build a vocabulary, or learning to write a coherent sentence. For others, it may be writing letters to heal relationships. The steps taken during the beginning stages may or may not be the same as the steps taken during the latter stages. By taking a deliberate course of action, an individual can cross the chasm from where he stands today to where he wants to be tomorrow.

Accountability: Those who follow the Straight-A Guide to success use strict accountability logs. Rather than polluting the air with happy talk about what they’re going to do, individuals on the Straight-A Guide set clear goals within each value category that defines success for them. In my case, it was important 1) to educate myself; 2) to contribute to society; and 3) to build a support network of law-abiding citizens. I defined success within each value category. I could show my commitment to education by earning university credentials. I could show contributions I was making to society through published writings. I could show my commitment to building a support network by bringing 10 mentors into my life. Accountability logs ensured that I could measure the progress that I made each day toward those clearly defined goals.

Awareness: By following the principled, deliberate path to success through struggle, an individual keeps himself aware of opportunities he can seize or create out of the same meager resources that are available to anyone else. He can position himself for the prison job that will allow him time to study; he can maneuver his way into the right quarters assignment; he can understand how to apply the SWOT plan to success, managing strengths and weakness, assessing opportunities and threats. Further, individuals who adhere to the Straight-A Guide increase awareness in others. As others perceive an individual’s deliberate, disciplined path, they develop a vested interest in helping the individual succeed. In my case, good opportunities opened through my commitment to living transparently. I was always in pursuit of clearly defined goals, taking incremental action steps. That Straight-A-Guide pursuit allowed me to build a substantial support network, opening more opportunities every day.

Achievement: To sustain high levels of energy and discipline, individuals must learn how to celebrate every achievement, no matter how small. Jail and prison communities are societies of deprivation, places that govern through the threat of further punishment rather than the promise of incentive. Yet individuals who live transparently, always driving toward the next goal, develop an intrinsic motivation. They learn to expect interference and obstruction from the negative environment, yet they succeed anyway, advancing inch-by-inch toward all that they can become. By stating goals clearly, they can reverse engineer their way to success, celebrating each incremental milestone that they reach along the way.

Appreciation: Finally, by living in accordance with the Straight-A Guide, individuals learn to express gratitude for all of the blessings they receive. Resources are all around, but those who choose not to live disciplined, deliberate lives fail to grasp their value. With all of the noise and negativity of confinement, it’s easy for people in prison to look, but not see; to hear, but not listen. When an individual knows how to define success with values, and when he understands how to set clear goals, he will develop a higher skill set in making the most of resources. My transformation began by flipping through the pages of a story on the life of Socrates. That message inspired me, giving me the drive to make progress while climbing through a quarter century of confinement, always in a state of gratitude for the blessings that I continued to will into my life. I appreciate all that I learned from the wisdom of others.

Anyone who succeeds follows the same deliberate path that I outlined as the Straight-A Guide. Yet many who are trapped in adversity fail to see it clearly. The strategy empowered me through a 45-year prison term, but it was equally applicable to anyone who endured the challenge of adversity. Those who make a 100 percent commitment to returning to society strong, as law-abiding, contributing citizens, could enjoy the same successful transformation. Success does not follow by accident, but instead through the deliberate, disciplined choices we make.

Had I known that perspective sooner, at the time of my arrest, I would have made different decisions from the start. Rather than continuing the lie, I would’ve accepted responsibility. I would’ve expressed remorse. Then I would’ve begun the process of rebuilding my life in a deliberate, disciplined way. Such a perspective likely would’ve resulted in my receiving a sanction that was far less severe than the 45-year term a federal judge deemed appropriate in my case.

As an aside, the judge imposed my sentence during the “old-law” era, before sentencing guidelines. The law at that time allowed me to satisfy my obligation to the Bureau of Prisons after 26 consecutive years, including a final year in community confinement, so long as I avoided disciplinary infractions.

I am now on the other side of that sea of adversity, in the process of building a career around all of my experiences. In fact, Federal Prison Authorities released me on August 12, 2013 and only 17 days later, on August 29, 2013, I began teaching as a lecturer at San Francisco State University. This letter is like a message in a bottle that I’m sending out to anyone facing troubles with the criminal justice system. I urge you to make the right decisions now. Accept responsibility and find your way back toward the right way. Society will welcome you on the other side.